You’d be hard-pressed to find a better person to take the ceremonial first kick at the Earthquakes-Seattle Sounders game Saturday at Levi’s Stadium than Dick Berg.

Berg, as the Earthquakes first GM in 1974, helped the team average 16,576 fans a game during its rousing debut season at Spartan Stadium in the North American Soccer League.

The former Stanford quarterback also helped the 49ers move from Kezar Stadium to Candlestick Park in 1971 as the 49ers marketing director. So who better to christen the 49ers new home, which will serve the Earthquakes home-away-from-home each season, than Berg? He is connected to the evolution of both organizations.

What a kick.

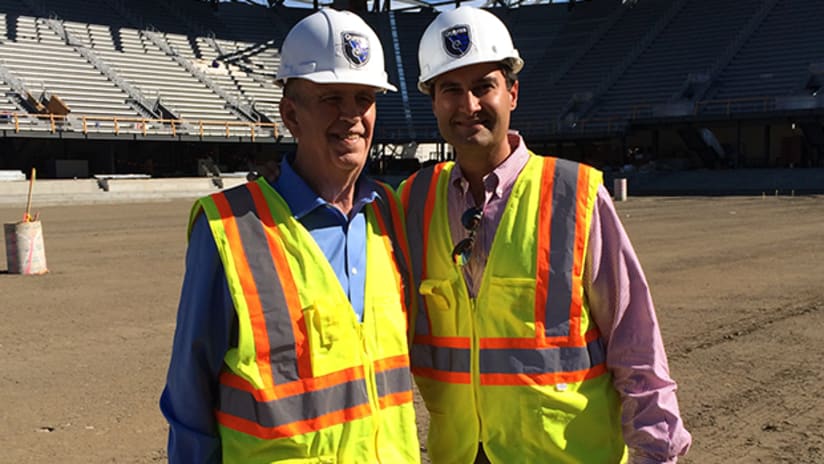

“I’m 71, but feel like I’m 35 again,” said Berg, a Florida resident who got a tour this week of the Earthquakes new stadium in San Jose, with club president Dave Kaval.

Indeed, it’s a nostalgic time for Berg and his son, Brady, a San Francisco attorney. Brady has had a lot to soak in. He attended one of the 49ers’ final games at Candlestick Park, and talked to his dad during his recent visit to the area about attending a football game at Levi’s Stadium.

“He has an affinity for stadiums, having spent his whole life around them,” Brady Berg said.

Brady’s soccer senses have been on high alert with the Earthquakes’ reemergence with a grassroots approach, Major League Soccer’s growing popularity and the success of the World Cup.

“And then I heard that the Earthquakes were going to open up the first game at Levi’s: ‘Oh my gosh, this is a trifecta:’ just connecting all the dots.” Brady Berg said.

Remember that it was Dick Berg who refused to let the NASL place the original Quakes in San Francisco. He saw a strong fan base in the South Bay and on the Peninsula, not San Francisco. He also gave the club its name, Earthquakes. The San Jose Mercury News encouraged fans to send in suggestions for the name of the franchise, and Berg selected Earthquakes.

“I’m just proud as punch that I had a little thing to do with how it all started, and maybe had a good enough track record that people started to copy it,” Dick Berg said. “That’s the biggest compliment that you can get. I couldn’t be prouder of how it appears (pro soccer) has now started to reach its adult life. I might have had him from about 4 years old up until maybe 14, and now they’re adults. It’s just great to see.”

Berg has spent the past 25 years living in Miami, after working in London with the Michael Jackson family, helping them raise about $12 million to bring Gold’s Gym fitness centers all over Europe, he said. A cold, wet winter in London drove Berg to start looking for a warmer climate.

“Somebody said to us, ‘Miami is the place to go. Everybody in England goes to Miami,’” Berg recalled. “I said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me?’ We took off and landed in Miami, and sure enough it was about 85 degrees, and I said, ‘I’m never leaving, and I haven’t.”

Berg left the 49ers in 1974 to join owner Milan Mandaric’s Quakes. He served as the club’s innovative GM for four years, becoming the talk of the NASL with his “beat the bushes” marketing style, in which the club sent players to soccer fields and parks all over the Bay Area to shake hands and make lasting friends. He made Quakes games fun-filled spectacles, the original entertainment sometimes overshadowing the games.

Berg had no background in soccer before making the bold move to professional soccer. In fact, when he was first approached about bringing the sport to the Bay Area, Berg had this skeptical response:

“Tell me about the sport: Is the ball pumped or stuffed?”

But Berg knew how to sell the sport to an American audience. He read the room well, from a marketing standpoint. Brady Berg compares his dad’s “eyeball-to-eyeball” marketing style to pre-Twitter or pre-Facebook, in which people would literally tell a friend, rather than click “like” or re-tweet it.”

Berg is happy to see the game flourishing today in the South Bay, especially considering the stand he took for San Jose 40 years ago.

“Lamar Hunt came out and had a meeting with me, and I flat told him what the deal was: ‘I probably know this area better than anybody. If you do the smart thing and put this thing in San Jose, you’ll probably get 15,000 to 20,000 a game.’ They’d never had a crowd of over 3,000 for any of their games (in Dallas) for the last seven years. I said ‘15,000 to 20,000.’ They all looked at me like I was crazy, and I said, ‘That’s my terms. If you let me do it San Jose and the Peninsula, then we might talk about it.’”

They accepted his terms, and Bay Area soccer history was made.

“So that’s why I left the 49ers,” Berg said. “Everybody at first said I was sillier than a loony tune, but it couldn’t have ended up any better in San Jose.”

After being the Quakes’ GM for four years, Berg joined forces with the Dallas Tornado franchise headed by Hunt, who’d been impressed with his work in San Jose. Berg helped Dallas succeed at the gate, after convincing Hunt to relocate from vast Texas Stadium to a smaller venue on the campus of Southern Methodist University in a Dallas suburb.

“He was playing in the big stadium and it was sort of a joke,” Berg recalled. “Anyway, our first year we averaged over 14,000 in Dallas, and then our next year we got to 17,000. Soccer was now on the map in Dallas. … Lamar said, ‘Thank you.’ I told him I had to go back to the Bay Area, and we started one more team, the Oakland Stompers. That was my last one. I guess in about 1980, I sort of resigned from soccer and went away on a two-year trip around America, and I wrote a book about it.”

Berg’s folksy, but effective, marketing style was shaped by his time with the Seattle SuperSonics’ NBA franchise, after he attended law school at the University of Washington. He also worked for the Seattle Rangers of the Continental Football League.

“We needed to go wherever people were,” he said of his marketing approach. “You might say ‘plant the flag’ for a day and let people come around say ‘hello’ to a professional athlete, which there weren’t many of in those days in Seattle. I still believe that it’s the only way to start a franchise and keep ‘em going.”

He employed the same mindset with the Earthquakes, to great effect.

“Everybody else in the league was buying advertising,” he recalled. “I would say that’s the big evil. … You’re just wasting money. Put that same amount of money in getting people out talking to people, and they are going to tell people.”

-- Richter Media